By Joseph Anuga

I remember seeing pictures on Cable News Network of the carnage brought upon defenseless people during the 1994 genocide in Rwanda and thinking that as a result of the pure evil on display, ethnicity (or what is called tribalism) as a foundational principle for organizing political activity in Africa was totally discredited. That it would be difficult to ignore the great potential for evil that relating to people on the basis of ethnicity, a thing that they could not change predisposed all of us human beings to. At the time I was convinced that going forward, patterns of relationship among Africans would increasingly be oriented towards engaging each other through our minds and carrying out a dialogue of ideas with one another. That we would become more focused on cooperating with one another rather than drawing impassable lines that only lead to the possibility of conflict with one another and instill in us a zero-sum mentality. In my mind at the time, I was hopeful (even sure) that Africa could learn from the Rwandan experience just as Europe learnt from the Holocaust during the Second World War. I lived my life on the basis of this conviction: that relying on primordial divisions to relate with one another in the public sphere in Africa was coming to an end at the time. I believed that it was coming to an end because of the potential for violence and zero-sum calculations that it imposed upon those who espouse it. Despite many reasons for me to change my worldview at the time (such as the many riots and ethnic conflicts around Nigeria), I persisted in it till the rude awakening of September 7th 2001 in Jos the capital of Plateau State in central Nigeria. This was the day the violence leading to the deaths of hundreds and the destruction of property worth millions broke upon the city of Jos and persisted for over a week. I was caught up in one end of the city and had to traverse its length from the northern tip of the city to its southern extremity and I ended up staying the night at a friend’s home.

Reaching home the next day I saw the carnage from the day before and I realized that the evil in men’s hearts would never be exorcised through revulsion at the effects of evil acts. That no matter how sordid the crime may be, the ideas that drive the mindset of the criminal is here to stay. That no matter how repugnant the outcome of categorizing people on the basis of characteristics they cannot change may be, those who benefit from such an arrangement would perpetuate it if they believe they can gain from it.

This way of seeing things changed my assessment of human nature. I realized that people are not inherently virtuous but rather that decency and kindness are traits that can only be reinforced with conviction and practice. Seeing that people’s inclination is towards evil, I also realized that ignoring warning signs that the designs of evil people are about to burst out of the pipeline is very foolish and is a form of evil too. In addition to this I came to understand that when evil is put together as a policy for action, many perpetrators actually believe that they are doing a good thing as they kill the defenseless and innocent in the name of one set of ideas or another.

“The lessons from [Rabeh Fadlallah’s 19th century conquest of Borno] for the current situation in Northern Nigeria and the refusal of the elite from the areas controlled by the former Sokoto Caliphate and the Sheikdom of Bornu should be clear to those among them that have ears to hear. It has not yet occurred to them that their enemies are not their fellow Christian citizens in Nigeria nor is it British colonialism which has been dead for almost sixty years. Their enemy is within – Their refusal to come to terms with the most effective ingredients that make for power in the global system in the 21st century is their next great enemy.”

I saw that usually the easiest way to judge people’s inclination is to understand if they put ideas over persons (in other words if they didn’t care whether the ideas they held could lead to the suffering and death of innocent persons) or persons over ideas such that they recognized that for ideas to be even considered, they had to protect the innocent from harm and were oriented towards the preserving of vulnerable human life.

These considerations didn’t mean that I could not see that political expedience generally colored how people viewed the ideas that they approved of and held. I could also see that political expedience cannot be reasoned with once it is grasped by individuals and groups that they stand to benefit from the direction of given political outcomes that those urging caution are unlikely to benefit from. It was clear to me that to the extent that perceived interests drove political calculations, unless these interests are properly interrogated with the goal of preventing evil outcomes, only a winner takes all attitude to politics would do in most circumstances.

From these considerations it became easier for me to see that it takes a willingness to recognize in all human beings equal participants in our collective heritage to overcome the idea that in our relations with one another one’s gain must be another’s loss. It also became clearer to me that frameworks that develop patterns in which we can all win should be the goal of political activity in a mature world. I still think that in a mature world, humans will reject fratricidal conflicts with one another and prioritize cooperation and the peaceful processing of conflicts. Maturity in this context is not one of the characteristics of Northern Nigerian at the start of the second decade of the 21st century.

The story of the development of human civilizations from the distant past shows that different people manifest lessons from history in different ways and they all have their reasons for doing what they do. This in many ways determines the nature of the society that emerges as history unfolds. It also helps one understand and interrogate the choices made by people in specific societies and engage them with realistic expectations. Without a good grasp of how a situation involving persons with free will came to be, it will be very difficult to posit an alternative that can grant better outcomes to those people dealing with self-inflicted hardships. This is because in many instances they will not believe that the hardships are self-inflicted or that there are any plausible alternatives to the trajectory that they are on.

“When all these are taken into consideration one can easily see why holding that the ruling elites in Northern Nigeria are acting out a script that reads like a monumental tragedy is not really outlandish. When polities do not innovate and grow, they lend themselves to decay. The ideas around which they choose to hinge the process of decay can include but are not limited to identity politics focusing on things like ethnicity and religion; prioritizing primitive resource accumulation by governing elites in a prebendal fashion over production of globally competitive services and goods by the creative element of the population….”

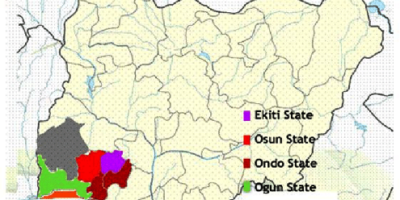

These perspectives when applied to Northern Nigeria make it clear that what has been unfolding here for decades is nothing but a human tragedy of monumental proportions that does not have to be this way. In the first place, and using statistics from the National Bureau of Statistics and the official conversion rate of 385 Naira to 1 US Dollar, the per capita GDP of the six geopolitical zones in the country are as follows southwest $ 4,182; south-south $ 1,959; southeast $ 1,503; north-central $ 1,288; northeast $ 847 and northwest $ 635 respectively. Only the northwest and northeast have per capita GDP rates at below one thousand US Dollars. In fact if the northwestern and northeastern zones are excluded from consideration, Nigeria will be a middle income country with one of the highest GDP per capita in Africa at USD$ 2,046. This shows that there is a massive failure of leadership in these northern zones compared to other zones in the country.

In addition to these, if the data on deaths by terrorism and banditry is considered these two zones again stand out as those with the largest incidence of these activities. Unemployment and infrastructural decay is also more heavily represented in these zones than others in the country. Just name the indicator for societal failure with regards to material development and the two largest zones (the northwest and the northeast) in Northern Nigeria will provide leadership with a significant gap over other zones.

The tragedy is that it doesn’t have to be this way and the way out is fairly easy to attain if the leadership in the area is willing to confront some hard truths. The first is that the response to colonialism by various people ended up determining how effectively they could cope with the postcolonial world. The responses by different people were conditioned by the different circumstances in each social formation at the time of their colonization which in turn played an important role in how their ruling elites dealt with the postcolonial world. Secondly, a proper assessment of the position of local conditions in relation to the prevailing ideas and concrete alternatives in the international system is not just necessary but required for developing effective responses to societal challenges by ruling elites on behalf of the people they rule. These two considerations give us vital insights to unlocking the current self-inflicted hardships permeating Northern Nigeria.

In the first place by the time of colonization in the last years of the 19th and the first few years of the 20th century, the two largest and populous political systems in Northern Nigeria (and all Nigeria for that matter) were the Sokoto Caliphate and the Sheikdom of Bornu. Both of these had their center of social and political gravity in the northwestern and northeastern zones of what would become Nigeria respectively. None of these political systems were threatened by any pre-colonial polity in what was to become Nigeria and the foundations of their military power were way above the capability of any other polity in Northern Nigeria before colonialism. Needless to say they were both Muslim polities.

They were already almost a century old by the time of their incorporation into the British Empire by 1903. Even then their autarkic nature and slow pace of innovation was making them obsolete in so far as the correct assessment by their leaders of their position in relation to the prevailing ideas and capabilities in the international system was concerned. Compared to a polity like the Benin Empire of the time, their military forces were painfully obsolete. They relied on massed cavalry at a time when the Benin kingdom had already transformed its military units from massed cavalry into gun and cannon formations as we see from the accounts of the British conquerors of Benin in 1897. The northern polities relied on walled cities to force a siege by the enemy at a time when explosives that could batter down those walls in hours had already been invented. This was one reason why the British force found it so easy to capture Kano in 1903.

However their greatest weakness was that culturally their ruling elites continued to compare themselves to the weaker polities around them and feel superior to these rather than seek to understand the basis for continuing changes in the ingredients of power in the international system. Such an assessment was not beyond the capabilities of either the Sokoto Caliphate or the Sheikdom of Bornu as Muslim polities. From the contacts they made during the annual Hajj, they could easily send embassies to Turkey the leading Muslim power at the time, or to Iran, Pakistan and even use North African Muslim nations such as Egypt or Morocco to create a mechanism to help them gauge the nature of developments in the international system of the late 19th century. Inevitably the complacent attitude of the rulers of these polities made them misconstrue the nature of the threat their societies were exposed to.

When the threat to their very survival initially came it was not from the Western powers but the rival Muslim polity of Wadai ruled by Rabeh Fadlallah. He attacked and conquered Bornu and would likely have had a victorious march to Sokoto if he had not decided to face the French before dealing with the Sokoto Caliphate. Rabeh had correctly assessed that military power in the late 19th century was more easily projected using European manufactured rifles and canons than massed cavalry and that sieges were more easily won using modern explosives than sending in infantry on ladders. At least on the military front, he had done his homework way ahead of the Sultans in Sokoto and the Sheiks in Bornu.

The lessons from this for the current situation in Northern Nigeria and the refusal of the elite from the areas controlled by the former Sokoto Caliphate and the Sheikdom of Bornu should be clear to those among them that have ears to hear. It has not yet occurred to them that their enemies are not their fellow Christian citizens in Nigeria nor is it British colonialism which has been dead for almost sixty years. Their enemy is within.

“If the northwestern and northeastern zones are excluded from consideration, Nigeria will be a middle-income country with one of the highest GDP per capita in Africa at USD$ 2,046. This shows that there is a massive failure of leadership in these northern zones compared to other zones in the country.”

It starts with the willful refusal to recognize that their response to colonialism which entailed the exclusion of the most effective tools for the spread of Western insights in science and administration represented by the Western Christian missionaries set them back in comparison to other comparable Muslim polities that suffered colonialism too. Most other Muslim polities that were colonized were able to quickly make the distinction between what is Christian in the curriculum and what is applicable to their conditions that wasn’t necessarily Christian. In places like Turkey (which was not colonized), Egypt, Pakistan, Indonesia and so on, Muslim rulers developed insights into the foundational principles of Western power while engaging their essence in a dialogue colored by Islam and not Christianity.

Their refusal to come to terms with the most effective ingredients that make for power in the global system in the 21st century is their next great enemy. There have been significant changes in the ingredients of power in today’s world when compared to pre-colonial times. An important marker of sustainable power in the world today is the ability of political rulers to deploy effective administrative capacity to create macroeconomic stability for their countries. This in turn implies that they also integrate ideas that strengthen the rule of law, due process in politics and judicial activity while entrenching effectively principles of human rights in the process of governance. These combined with commitment to freeing economic activity around markets that are regulated to prevent them becoming simply mechanism for exploitation constitute the core for creating and sustaining power in any polity in the world of the 21st century. Anything less dooms both the rulers and the ruled to a fate that guarantees that they will collectively fall under the control of other polities that have done their homework in this regard.

“Using statistics from the National Bureau of Statistics… the per capita GDP of the six geopolitical zones in the country are as follows southwest $ 4,182; south-south $ 1,959; southeast $ 1,503; north-central $ 1,288; northeast $ 847 and northwest $ 635 respectively. Only the northwest and northeast have per capita GDP rates at below one thousand US Dollars.”

When all these are taken into consideration one can easily see why holding that the ruling elites in Northern Nigeria are acting out a script that reads like a monumental tragedy is not really outlandish. When polities do not innovate and grow they lend themselves to decay. The ideas around which they choose to hinge the process of decay can include but are not limited to identity politics focusing on things like ethnicity and religion; prioritizing primitive resource accumulation by governing elites in a prebendal fashion over production of globally competitive services and goods by the creative element of the population; throwing at and tying national capital to recurrent expenses rather than investing in the future through properly funding education, health services or modern infrastructure. All these considerations are on open display in the processes being coordinated by the ruling elites in Northern Nigeria.

Nigeria is now the poverty capital of the world and Northern Nigeria particularly the northwestern and northeastern zones are the core areas propping up the incidence of poverty in the country. These zones also exhibit the most prevalent cases of dysfunctional relations in the development process with very high propensity for violence on a large scale (via insurgency, banditry, ethno-religious conflicts, kidnapping and so on), decay in infrastructure, high unemployment, low enrollment of children in schools, inadequate health care delivery and high incidence of infant mortality among many other indicators of material development.

“Nigeria is now the poverty capital of the world and Northern Nigeria particularly the northwestern and northeastern zones are the core areas propping up the incidence of poverty in the country. These zones also exhibit the most prevalent cases of dysfunctional relations in the development process with very high propensity for violence on a large scale (via insurgency, banditry, ethno-religious conflicts, kidnapping and so on), decay in infrastructure, high unemployment, low enrollment of children in schools, inadequate health care delivery and high incidence of infant mortality among many other indicators of material development.”

Despite all these, Northern Nigeria is blessed with massive agricultural resources, great potentials for the development of tourism through its rich multi-ethnic and multi-cultural heritage (as well as its climatic zones stretching from the Guinea savannah south of the Benue and Niger rivers to the Sahel savannah covering the expanse from Sokoto to Bornu around the Lake Chad area and including temperate climatic zones in the Jos and Mambilla plateau areas); its rich endowment in solid mineral resources (including gold, uranium, tin, columbite, tantalite among many others), its great potentials for the generation of hydroelectric power as well as irrigation and its teeming youthful population that can spur a massive investment framework in education if adequate resources are invested in the sector.

What is clearly lacking here is the visionary leadership that can turn the aggregation of resources into patterned relations of shared material development for all the citizens of Nigeria in general and Northern Nigeria in particular without playing partisan politics with issues like religion or ethnicity.

Joseph Anuga, lecturer at the University of Jos, is expert on International Economic Relations, Corruption, and International Political Economy.