By Aboubakr Kaira Barry, CFA

Congratulations on your recent appointment as President of the African Development Bank (AfDB). I am writing to share four critical insights from my analysis of AfDB’s financial statements from 2005 to 2024 and to offer constructive suggestions for improvement. These two decades encompassed both the global financial crisis (2008/2009) and the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, each of which impacted the Bank’s operations.

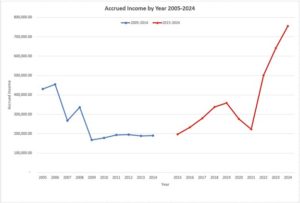

1. Disparity Between Cash Collected and Reported Profits

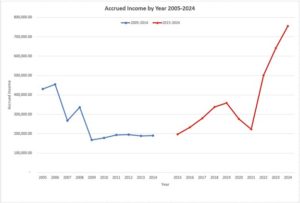

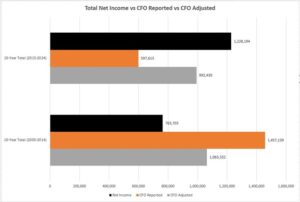

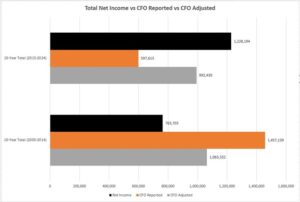

From 2015 to 2024, the Bank reported profits of UA1.2 billion (UA, or Unit of Account, is equivalent to approximately $1.44 as of July 2025). During this period, accrued loan income receivable (loan income recognized as profit but not yet collected) increased 3.8 times, rising from UA197 million in 2015 to UA756 million in 2024. This growth of UA558 million equals 45% of the total profits reported over the past decade. By comparison, from 2005 to 2014, the Bank declared profits of UA763 million, while uncollected loan income dropped by 56%, from UA431 million to UA191 million.

Comparing net income to cash from operating activities (CFO)—which shows cash received minus cash payments related to core operations—reveals a substantial gap. From 2015 to 2024, CFO totaled UA597 million, compared to UA1.4 billion from 2005 to 2014. After adjusting for a UA394.6 million reverse repo transaction (a short-term collateralized loan recorded as a 2014 operating inflow and 2015 operating outflow):

– Adjusted CFO for 2015–2024 rises to UA994 million.

– Adjusted CFO for 2005–2014 falls to UA1.1 billion.

Given the flexibility of accounting standards, it is prudent to compare net income with cash from operations over time to determine the extent to which paper profits convert into actual cash. The notable rise in uncollected income suggests a need for an independent review of the loan portfolio and loss reserves to confirm accuracy.

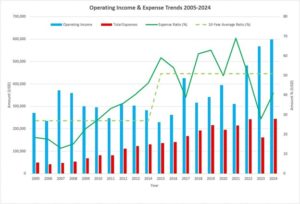

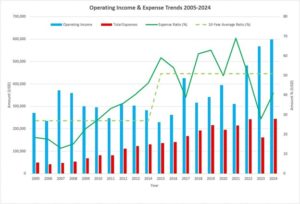

2. Escalating Administrative Costs

The Bank experienced a significant increase in administrative expenses, directly reducing funds available for essential development initiatives. From 2015 to 2024, administrative costs averaged 51% of operating income, up from 27% in the prior decade. Income allocations approved by the Board of Governors for strategic initiatives totaled UA788 million, just 56% of the previous decade’s total (UA1.4 billion).

3. Inefficient Capital Utilization

The Bank’s average equity increased by 71%—from UA4.9 billion (average for 2005 to 2014) to UA8.4 billion (average for 2015 to 2024). Net resources transferred (NRT) to countries—defined as total disbursements minus repayments—increased by 59%, rising from UA7.6 billion to UA12.1 billion over the same periods. Consequently, NRT per UA of capital fell from UA1.55 to UA1.44, representing a 7% decline in efficiency—even as indicated above the ratio of expenses to operating income almost doubled.

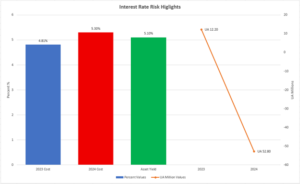

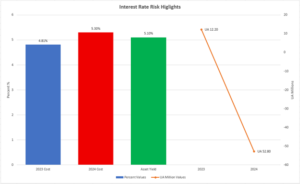

4. Heightened Exposure to Market Risk

The Bank uses interest rate and currency swaps to manage risk. By 2024, total borrowing costs—including swaps—rose to 5.30%, up from 4.81% the previous year. Investments using market-sourced funds (UA26.4 billion) generated just a 5.10% return; consequently, 61% of total assets produced a UA52.8 million loss, compared to a UA12.3 million gain the previous year—a negative swing of UA65.1 million.

Rising interest rates, which are likely as explained later, could worsen these losses. This is exacerbated by the structure of the swap agreements.

The Bank must: a) pay an adjustable rate, which reached 4.74% on December 31, 2024, on UA27 billion of off-balance-sheet exposure; and b) receive a fixed rate of 2.38% for the next five years—only half of what it pays, since rates have increased since the swap began. In market-based swaps, the amounts exchanged are equal at the start date.

As of December 31, 2024, the Bank expected to pay UA1.2 billion more on swaps than it will receive—equal to 10% of total equity, compared to 7% at the Asian Development Bank. Any further rate increases could exacerbate this situation; for example, a half-percent rise in the adjustable rate would add UA135 million in expenses.

The Financial Times (July 26, 2025) reports that OECD bond issuance by member countries will rise from $14 trillion in 2023 to $17 trillion in 2025, with 45% maturing in 2027. These will need refinancing at higher costs, as most were issued during low-rate years, suggesting that the Bank’s market-related financial risks may persist or increase in the near future.

While the Bank remains well-capitalized and faces no immediate financial stress, Warren Buffett has warned that derivatives can be “weapons of mass financial destruction.” It is vital to engage independent experts to examine risk management and hedging strategies to ensure stability.

Four Recommendations

Given these financial risks—particularly the gaps between reported profits and cash collections, and the rise in market risks—the Bank must act proactively to protect its balance sheet and enhance efficiency. I propose:

1. Independent Financial Evaluation

Hire an independent consulting firm to review the quality of the lending portfolio, the adequacy of loan provisions, and the Bank’s risk management practices, including the use of derivatives. This assessment will help you implement necessary corrections early in your tenure.

2. Strategic Reassessment

The late Peter Drucker, a renowned management expert, advised leaders to periodically ask: “Would we do what we’re doing now if we weren’t already doing it, knowing what we know today?” The Bank should apply this question to its operations, using it to develop a revised strategic plan focused on its comparative advantage.

3. Performance Management Framework

Many strategies fail due to poor execution. I recommend inviting John Doerr, chairman of Kleiner Perkins and an expert on the OKRs (Objectives and Key Results) management system, to share his insights. He can help implement OKRs, which have driven success at Google and the Gates Foundation.

His book, Measure What Matters, shows how OKRs can keep organizations focused and accountable. Using this framework, each department can set clear, measurable objectives and key results aligned with overall strategy. It also includes a performance tracking tool that can provide real-time data on progress relative to expectations, enabling timely corrective action.

4. Leveraging Technology for Transparency

Implement blockchain technology to position AfDB as a transparency leader among multilateral development institutions. While capital growth has not resulted in proportional resource transfers, blockchain can provide real-time project updates and increase transparency by: a) giving all stakeholders—including citizens—secure access to project data; b) accelerating the resolution of bottlenecks via increased transparency; c) allowing for direct citizen feedback on project results.

For example, a beneficiary of an agricultural financing project could log in to check the disbursement status and provide feedback after project completion. This could gradually shift the development landscape from self-assessed impact to beneficiary-led assessment, improving project quality. A pilot in a tech-forward country like Morocco could serve as a model.

Blockchain will increase transparency and accountability, promote timely project execution, and set AfDB apart from its peers—making it a source of pride for Mama Africa.

The author is Managing Director of Results Associates, a consulting firm in Bethesda, Maryland, USA; former Director of Finance at the Islamic Development Bank; and former Senior Auditor at the African Development Bank. Longer version of this article including supporting data can be found on my LinkedIn page: linkedin.com/in/barry-ra